Disasters occur with almost unpredictable probability, even though some ideas about the regions of incidence and likely impact on likelihood are available in the scientific literature. In this lecture, I have taken a full view of six disasters that include hydro-geological, meteorological, climate based like floods and droughts as well as the biological holocaust of Covid-19 pandemic. The approach followed in this lecture is to analyse the occurrences, incidence, history and devastation caused by the disaster. The impact and policies to alleviate the effects are also discussed. The culture of disaster reliance is discussed at the end.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

I feel quite honoured to be invited to deliver this prestigious lecture on a subject that is quite close to my academic work for decades. I was very fortunate having not only worked when Professor L S Venkataramanan was at the ISEC as senior Professor and later on as Director of ISEC. I joined his research team on the “Dynamics of Rural Transformation” a project sponsored by ICSSR, spear-headed by Prof C T Kurien. The project was already quite delayed and Prof LSV wanted me to join in order to finish the work. We worked together and completed the project out of which I could publish one or two papers. Unfortunately, his ambition that we should publish a book out of this work and on our joint works on supply & demand projections of food grains in Karnataka remained unachieved. He had negotiated the publications with Late Shri Tajeshwar Singh of Sage publications but unfortunately before it could take final shape that fateful accident took him away. That was a great loss for the academic fraternity and personally to me, as he was quite an affectionate person in my life. I specifically chose this topic to deliver this lecture as I have worked for quite some time in the areas covering many of the aspects which touch the core of disaster management. I am trying my best to bring together my thinking over years as well as the major hypothesis of institutional participation in disaster management.

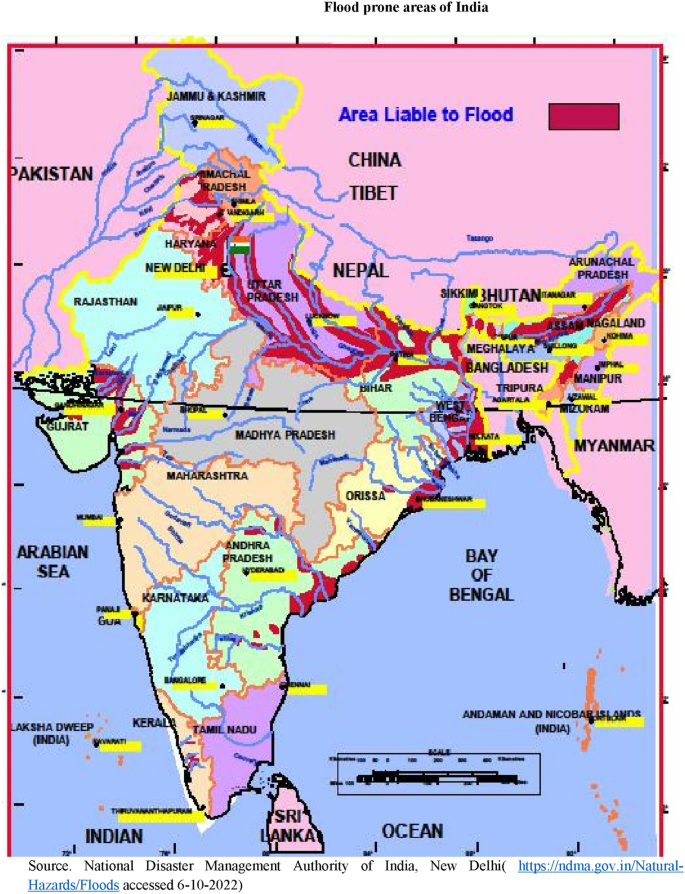

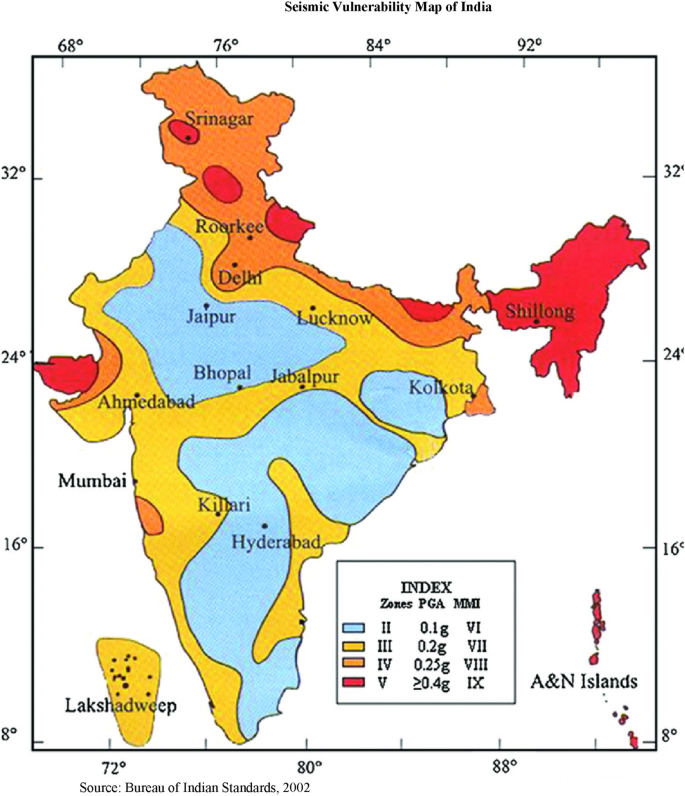

In the calculus of disaster management, it is essential to decipher the typology and intensity of the ensuing disasters. The Indian subcontinent distinguishes among others as one of the most disaster-prone area. More than 85% of India’s geographical area is prone to multiple hazards. Out of the total Indian states and union territories, almost three-fourth is disaster-prone (Shah 2011). More than 55% of India’s area falls under seismic vulnerability (high seismic zones III–V), about 65% face the occurrence of drought and then cyclones and floods threaten about 10% of the area. After the release of the IPCC reports, the link between disasters and climate change is being increasingly established (Shamsuddoha et al. 2013). The eastern coast is more vulnerable since the 2004 tsunamis in the Indian Ocean. The Government of India in the documents on disaster management in India noted that a disaster is an “event or series of events, which gives rise to casualties and damage or loss of properties, infrastructure, environment, essential services and means of livelihood on such a scale which is beyond the normal capacity of the affected community to cope with”. The UNISDR (2011) defined disaster as “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources”. Further, refining the concept, the Govt of India in 2011 defined it as “Disaster is also sometimes described as a catastrophic situation in which the normal pattern of life or eco-system has been disrupted and extra-ordinary emergency interventions are required to save and preserve lives and or the environment” (GoI 2011, p 4). A common understanding from the above is that a disaster disrupts normal human life without sufficient warning and causes huge economic and human losses. It resets the development clock in the affected regions a few years backwards.

Disasters certainly occur without much warning regarding their occurrence or the kind of havoc that they will leave around. It will certainly be futile to answer the question and reason for the causes of disasters since the advance prediction of disasters of all kinds has hoodwinked the best scientific brains of the world (Asimakopoulou et al. 2010). Certainly, disasters occur when there are significant changes in the holistic natural equation of the universe which includes biological entities, the earth, climatic factors and above all human interactions with many of the components of these elements. In the Indian Scriptures, it has been stated that there are five Maha-Bhootas (very crudely translated as five demons) that are responsible for cosmic creation (Gopal 1990, P.79). These five uncontrollable factors that dictate life on the earth are defined as Pruthvi (earth); Aaps (Water), Tej/Agni (Sunshine or Fire), Vayu (Air or Green House Gases), Akash/Dyaus (Space, Atmosphere, Universe) (indianscriptures.com). It has been stated in the scriptures that these are uncontrollable cosmic creations and hence need to be worshipped and pacified, (www.holybooks.com/wp-content/uploads/RigVeda.pdf). The interactions between these five and their subcomponents can further create abnormal natural events and human interaction with all these five uncontrollable factors sometimes increases the intensity of such abnormal events. These extreme events occur when humanity takes the naturalness out of nature (O’Keefe et al. 1976). Therefore, any event that occurs has a permutation of 120 multiplied by the innumerable geo-climatic zones and mega-human interactions in the world. This fact is truly multifarious and thus any catastrophe that occurs has a very thin, nearly unpredictable probability and is hence called a disaster. Mismanagement of these elements and disturbance to the base element equilibria are the main reasons behind every disaster. At times the disaster management bodies were not able to do anything to prevent deaths. Even a moderate earthquake of magnitude 6.0 on the Richter Scale in Sikkim in 2011 was a disaster, causing large-scale destruction and many deaths. There is little control that can be exercised over these events. The disturbance in the base element equilibria needs to be managed with human efforts. Even though forecasting the probability of occurrence is difficult, being prepared for extreme events is not impossible. Certainly, there have been many efforts towards preparedness for disasters and a list of many such requirements for avoidance and mitigation of disasters due to climatic changes are listed in the IPCC reports. In India, the Ministry of Home Affairs brought out an Act of 2005, a policy document in 2011 that was reviewed in 2013 suggesting a framework for the plan. Further, a Disaster Management Plan was brought out in 2016. However, it is a fact that disasters occur not simply due to disequilibria but more so due to under-preparedness and management failures of such events.

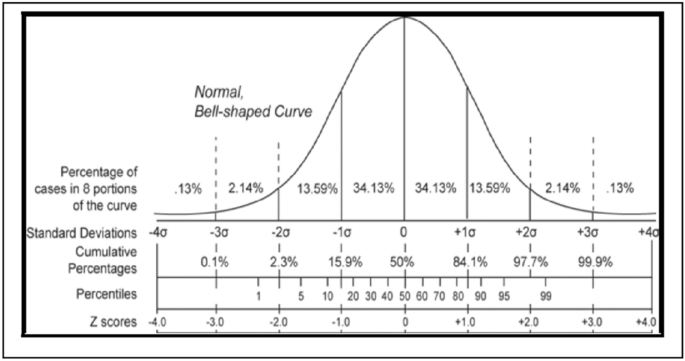

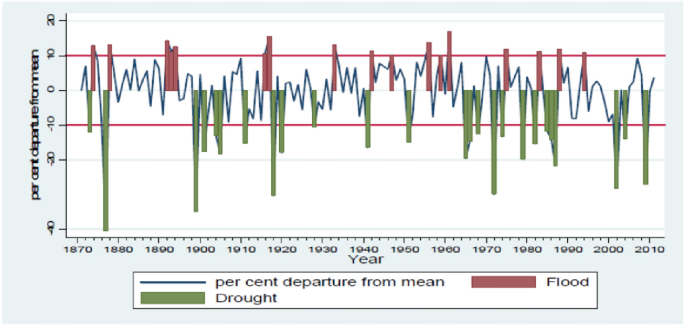

Understanding disasters, therefore, involves deciphering the complex interactions between a multiplicity of climatic and manmade factors with the environment and its components. Not all environmental and climatic variables need to behave normally across years and regions. There are always variabilities and these vacillations differ in their intensity across space and time. It is the intensity of these oscillations that distinguishes them from simple aberrations and normal behaviour to reach disaster or catastrophe. There is always a history of the probability of occurrence of most of these climatic events be it rainfall, temperature, pandemic, diseases, floods, droughts, tornados or any such things. The probability distribution of occurrences is shown in Fig. 1, which indicates the well-known normal probability distribution. This is a distribution of probabilities and standardized occurrences of the events. The most feasible probabilities are clustered in the centre having occurrences that are positive (favourable) and negative (unfavourable). The probability of the occurrences is spread on both sides and any events happening out of the normal (central bell shape) are not desired, whereas the events with probability falling within the central portion of the bell shape are desirable. The basic parameters of the normal distribution are that it has zero expected value and constant standard deviation.

The figure shows a bell-shaped curve having four segments on the negative side (left side) and other four segments on the positive side (right side). If we take any event which may occur on either of the sides, they differ from normal occurrences to abnormal occurrences. The normal occurrences are shown in the central portion of the normal distribution. The central portion indicates the normal behaviour of any phenomenon. Initially, the first departure segments on either side beyond one standard deviation away from the mean can be called “Mild shock or aberrations”. The “aberrations” are events that go slightly away from the central portion of the bell-shaped normal distribution. The central portion which ranges from − 1 to + 1 standard deviation (SD or α) and covers about 68.26% area includes all the events that come within the one SD of the mean or normal occurrence. These could be called mild shocks or adverse situations that are usually in the range of routine management techniques. The second group comes on the right, and the left side includes the fluctuations which go beyond one SD and extend up to 2SD on either side. These should be called aberrations and occur in the probabilities falling in that range of two standard deviations below or above the normal. These events cover 27.18% of the area and therefore will occur approximately at that probability of occurrence. The severe fluctuations come in the range of 2 to 3 standard deviation either below or above the normal occurrences. The Agricultural Commission 1976 defined severe fluctuations in this range of probability and demarcated the regions as susceptible to droughts and floods based on the probability of occurrence in the regions between 2 and 3 standard deviations on either side, and severe fluctuations and up into calamity when the occurrence takes place in the range of 3 to 4 standard deviations from the normal. The severity depends on the closeness of the event towards the border of four standard deviations on either side of the distribution. If we take the example of drought and floods, the first group within one standard deviation show a mild impact depending on the vulnerability of the region. The second group falling beyond two standard deviations on either side will result in a drought or flood situation depending on the closeness of the event to the point mark at three standard deviations. These should be called severe fluctuations and require immediate management on behalf of the policymakers. The calamity occurs when the events take place marking the fluctuations beyond three standard deviations, and the severity depends on the closeness of the event near the four standard deviation point. Such situations are cataclysmic situations and have to be dealt with very carefully as calamities. Any event that occurs at any point beyond the four standard deviation limits on either side requires preparedness as well as skills to deal with catastrophic situations. Such events occur with very thin probability and hence can result in a holocaust. In all these events, the role of administrative response is quite important and necessary to avoid loss of assets and life as well as ameliorate the suffering of the population. Therefore, it is a battle of wits between the learner and scientists and the natural events that require preparedness and management of the calamity.

The Disaster Management Act, 2005, defined disaster as “a catastrophe, mishap, calamity or grave occurrence in any area, arising from natural or manmade causes, or by accident or negligence which results in substantial loss of life or human suffering or damage to, and destruction of, property, or damage to, or degradation of, environment, and is of such a nature or magnitude as to be beyond the coping capacity of the community of the affected area” (GoI 2005). It is a sudden occurrence with a severe jolt that disrupts and destroys normal life and brings economic activities to a standstill, destroying the normal functioning of society and resetting the development clock.

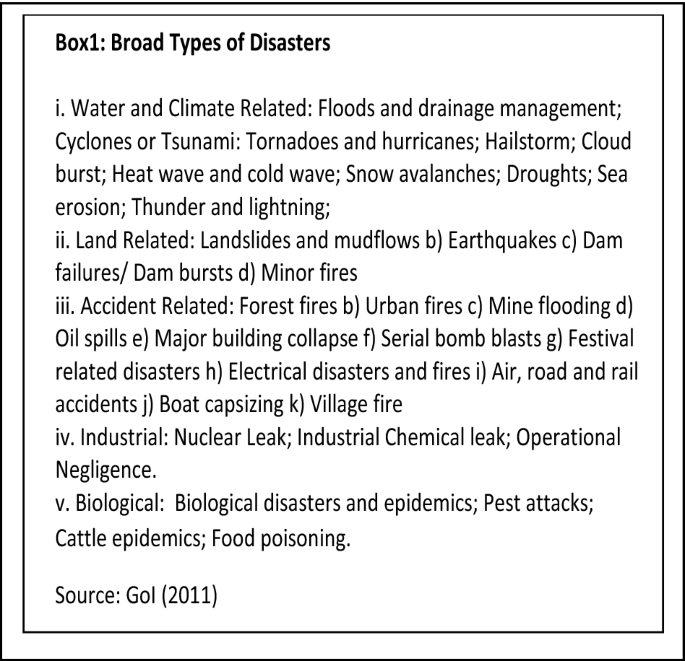

The administration of disasters is certainly a challenging job as the administrators do not get any warning and also have very little knowledge of the severity of the impact (Sharma and Kaushik 2012). The administrative response goes by the type of disaster, and it has been very clearly documented in the Disaster Management Manual of the Government of India, 2016. Broadly the type of disasters indicated there are shown in Box 1. These are classified according to the causes of disasters which is the usual way of classifying disasters across the world (UN and World Bank 2010; UNESCAP 2016). However, it is essential to understand that disasters do not strike uniformly across regions and humanity. The severe impact is felt in the most vulnerable regions, and hence, the impact gets weighed by the intensity of the disaster as also by the vulnerability of the region. The UNISDR/SDMC report (2014) gave a good framework for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. The calculus of disaster management, therefore, works on three important dimensions. First, the type and probable intensity of desire. Second, the vulnerability and the population of the region. Third, the main economic base of the region and its dependent activities matter the most. It was in 2001 that a High Power Committee of the Ministry of Home prepared a report about disaster preparedness in India (GoI 2001). There was no institutional set up for managing disasters in India till the 1990s and all calamities were handled with a “firefighting” approach in a great hurry. A disaster management cell was placed under the Ministry of Agriculture after the declaration of “International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction” (IDNDR) by the UN General Assembly and a series of disasters (like Latur Earthquake (1993), Malpa Landslide (1994), Orissa Super Cyclone (1999) and Bhuj Earthquake (2001)). The Government of India constituted a High Powered Committee under the Chairmanship of Mr. J.C. Pant in 2001.The Committee submitted a detailed report, and the recommendation was followed. Subsequently, the Disaster Management Division was placed in the Ministry of Home Affairs in 2002. Subsequently, the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (GoI 2005), was passed and the Act gave an elaborate framework for the Institutional set up to deal with such calamities.

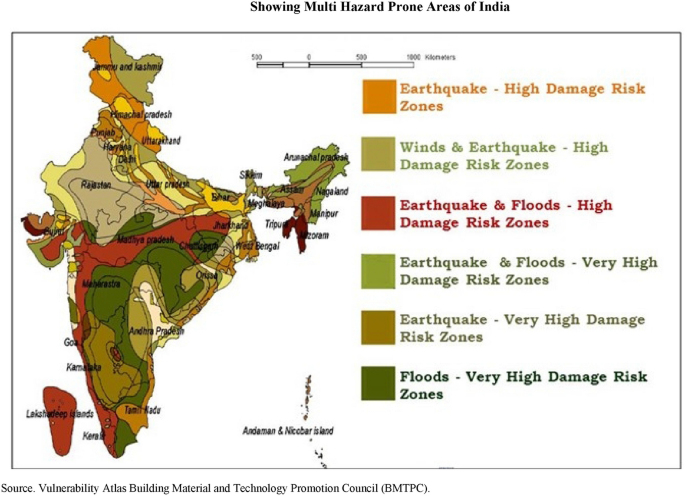

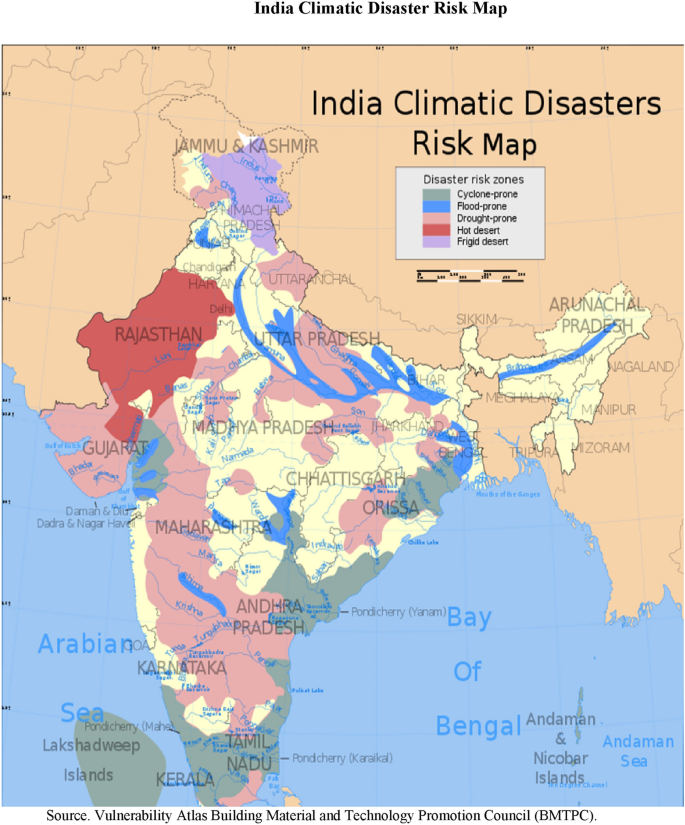

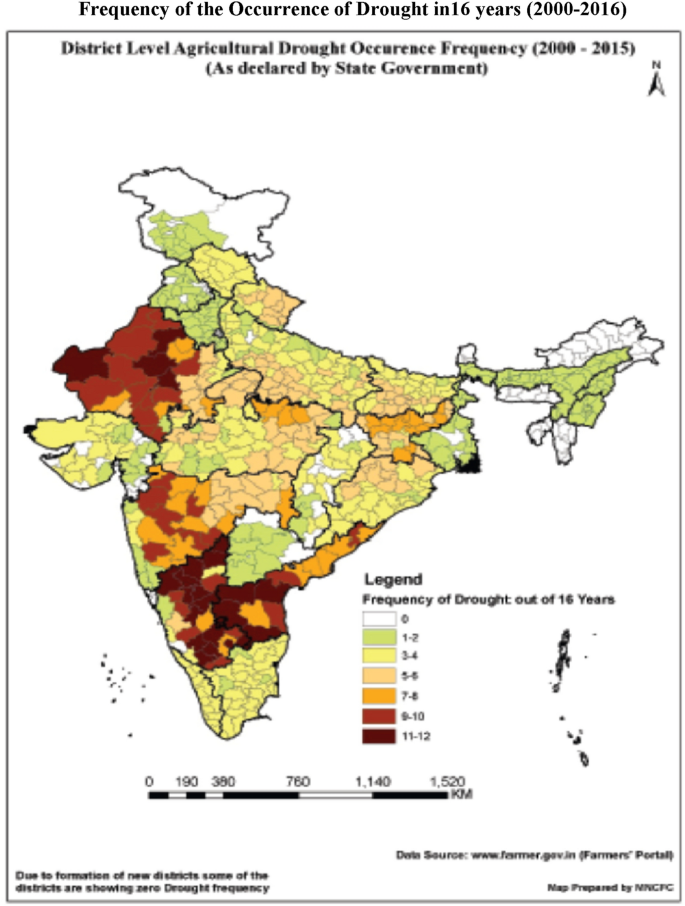

India’s hazard-prone area has been mapped by the Building Material and Technology Promotion Council (BMTPC) in their “Vulnerability Atlas of India” presented in Map 1 showing the multi-hazard zones of India. We have placed this map here to give a glimpse of the problem and the dimension of the issues to be tackled. BMTPC has done significant work in mapping the hazard-prone areas of India and mapped the information in policy convenient maps. It has been well documented in the BMTPC work that 85% of India’s area faces multiple hazard vulnerabilities. Almost 22 states are under the continued shadow of disasters of one type or other. The eastern and western coasts are vulnerable to weather storms on both the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea coast (Map 1). The eastern coast faces several sea initiated turmoil. About 8% of the coastal area is prone to cyclones. Droughts and floods are regular visitors in most of the states, especially in central India. It is seen that India has about 68% of its area categorized as “drought-prone”, and at the same time, about 12% of its area faces frequent floods. Acute seismicity resulting in earthquakes is confronted by almost 57% of the area that falls under the high seismic zone (World Bank 2010).

Any disaster causes not only huge material losses but also human and animal lives. However, these are not uniform across various typologies of disasters. The predictability, damage, loss of lives and material differs across disasters (Table 1). In many cases, all the economic activities come to a standstill and the government has to spend additionally to recoup the losses and bring back economic activities to normalcy. The World Bank report documented 73 such instances of natural catastrophes in just four years between 1996 and 2000 and reported direct losses on public and private economic infrastructure in India (UN and World Bank 2010). Similarly, vulnerability across states also differs significantly. Some states are well prepared to deal with such situations (Karnataka, Odisha, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh) with little warning, but a few others squarely face destruction (Table 2).

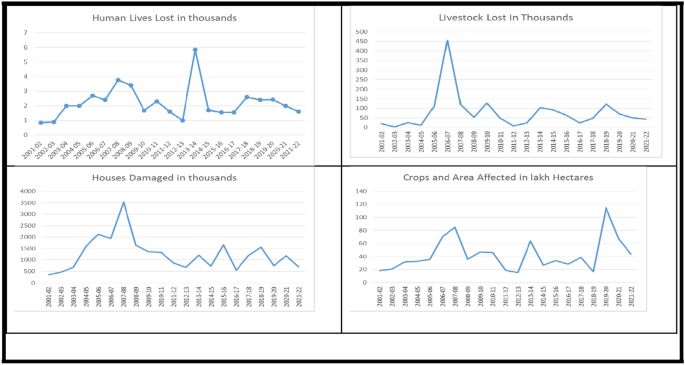

Broadly, disasters can be placed into six groups: (I) Water and Climate Related: (a) Floods and drainage management; (b) Cyclones or Tsunami, Tornadoes and hurricanes; c) Hailstorm; d) Cloud burst; (e) Heat wave and cold wave; Snow avalanches; Droughts; Sea erosion; Thunder and lightning; (2) Land Related: Landslides and mudflows (b) Earthquakes (c) Dam failures/Dam bursts (d) Minor fires; (3) Natural Accident Related: (a) Forest fires (b) Urban fires (c) Mine flooding (d) Oil spills; (4) Accidents due to Human errors: (a) Major building collapse (b) Serial bomb blasts (c) Festival related disasters d) Electrical disasters and fires e) Air, road and rail accidents f) Boat capsizing g) Village fire; (5). Industrial: (a) Nuclear Leak; (b) Industrial Chemical leak; (c) Operational Negligence and the last one are: (6) Biological: (a) Biological disasters and epidemics; (b). Pest attacks; (c). Cattle epidemics; (d).Food poisoning. Usually, these originate as natural hazards or human-induced vulnerabilities. These can also result from a combination of any of these. As indicated earlier, it is the non-normal behaviour of the “Pancha Mahabhutas” coupled with human interactions that result in these disasters. Most human-induced factors can worsen the negative impacts of a natural disaster. The UN Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also noted that human-induced climate change has a significant role in both the frequency and intensity of these episodes (Mall et al 2006, 2011a; b; Kelman 2008, 2009; Dhar 2010). At the policy level, the Government of India recognized the severity of the impact due to climate change even before 2001 and set in motion preparations accordingly (GoI 2008, 2012). IPCC (2013) brought forth the necessity of inter-governmental cooperation while keeping in view the probability of increasing disasters (Seidler et al (2018)). At about the same time, the Government of India appointed a task force to review disaster management in India and the task force gave clear guidelines which were followed in the Act (2005) and Disaster Management Plan that followed in 2016 (GoI 2013, 2016). While heavy rains, cyclones, or earthquakes are all extreme natural events, the impacts relate mainly to actions or inactions in human activity. Extensive industrialization and urbanization increase both the probability of human-induced disasters and the extent of potential damage to life and property from both natural and human-induced disasters. Climate change has also contributed to the severity and frequency of these events (UNISDR/SDMC (2014; Shamsuddoha et al 2013). In the first kind, we have hydro-meteorological disasters that cause significant damage to the ecology as well as human and animal lives. The economic impact of these disasters is quite significant. The impact of the four important components as recorded and analysed in the Ministry of Home Affairs of the Government of India, namely cyclones, tornadoes, whirl winds and floods as well as droughts, come under this severe most category. The second major cause is due to the changes in the geological patterns, especially reflected in earthquakes, landslides and avalanches are seemingly caused by geological causes, but the role of human activities in them cannot be undermined. The third typology of disasters is due to unpreparedness and failure to understand the pattern of natural events. Therefore, these are caused mainly due to the inaction of the State agencies and the response of the population. The last category includes biological disasters either due to human intervention or the intrusion of biological elements like viruses, bacteria or any such epidemiological events. These phenomena are of organic origin or carried by biological vectors, including exposure to pathogenic micro-organisms, toxins and bioactive substances. Major accidents due to the mishandling of chemicals, atomic energy or radioactive material also have a significant impact on human lives. It is, therefore, necessary to understand the mechanics of most of these disasters to equip and be prepared to meet the calamities for reducing the losses.

Disasters have different typologies. Among the disasters that we have taken for discussion in this lecture are cyclones or tornadoes, earthquakes, floods and droughts followed by the pandemic. It was necessary to keep the contours of this lecture limited to the available data and time at my disposal. Each one of the typologies mentioned above has a serious impact on human life and livelihood. Besides, most of them force to restart many developmental initiatives destroyed during the disaster. These include houses, roads, railway lines, bridges, factories, banking, trees, crops and many other things that come in the region.

Cyclones, thunderstorms and tornadoes are among the worst impacting events that come with little warning but visit frequently. The eastern coastline covering about 8% of the land is extremely vulnerable. It is estimated that approximately three cyclones visit the coastal line every year with varying intensity. Therefore, regions from West Bengal to Tamil Nadu are highly vulnerable. The west coast is relatively less vulnerable due to its geographical formation, but any event on that side of the sea cannot be ruled out. If the west coast gets any visitations of events similar to that on the east coast of India, the devastation and loss of life will be unparalleled. In the event of a fully developed cyclone, the coastal line also faces gales and strong winds; torrential rain and high tidal waves. As the storm surges, it destroys human habitations. Large human casualties take place as many times it comes without sufficient warning (Table 4).

Among the essential steps to improve the monitoring of drought situation, the first step begins with the formation of a contingency plan from the micro level aggregating to the macro level. This plan should be further totalled at the state level and must include all the requirements of data at the village level to understand the intensity and spread of drought. Principally, the data have to be collected on the rainfall incidence, variability, moisture index of the soil with the well spread samples, crop conditions, and socio-economic responses of the people. The Soil Health Card scheme followed recently in many States provides only scientific information about the soil on the card supplied to the farmer, which the farmer neither understands nor can take corrective action and therefore, these are of little use other than keeping them in the cupboard. Recently, a World Bank-funded project on Watershed Development in Karnataka emphasized the Land Resource Inventory Card (LRI) with huge funds invested at the behest of the World Bank. This is not the only a case of putting investment down the drain on half-baked expert advice. Earlier on the advice of the World Bank experts, vetiver grass was planted as a vegetative bund with large investments in Manoli, Kabbalnala, Maheshwarnala and Puruanala watershed projects. Unfortunately, not a blade of that grass is available today in any of these watersheds and the borrowed funds invested certainly went down in the soil (Deshpande 2022).

As a submission to the Agricultural Commission 1976, the Indian Meteorological Department prepared a map of rainfall failure zones across meteorological sub-divisions. These maps were quite useful in drought planning and preparedness. The probabilities of rainfall failures in different ranges across states were arrived at and that served as a basis for future planning presented in Table 11. The states could be categorized into five levels, namely: very rare; rare, frequent, very frequent and severely drought-prone based on the probability of failure of rainfall.

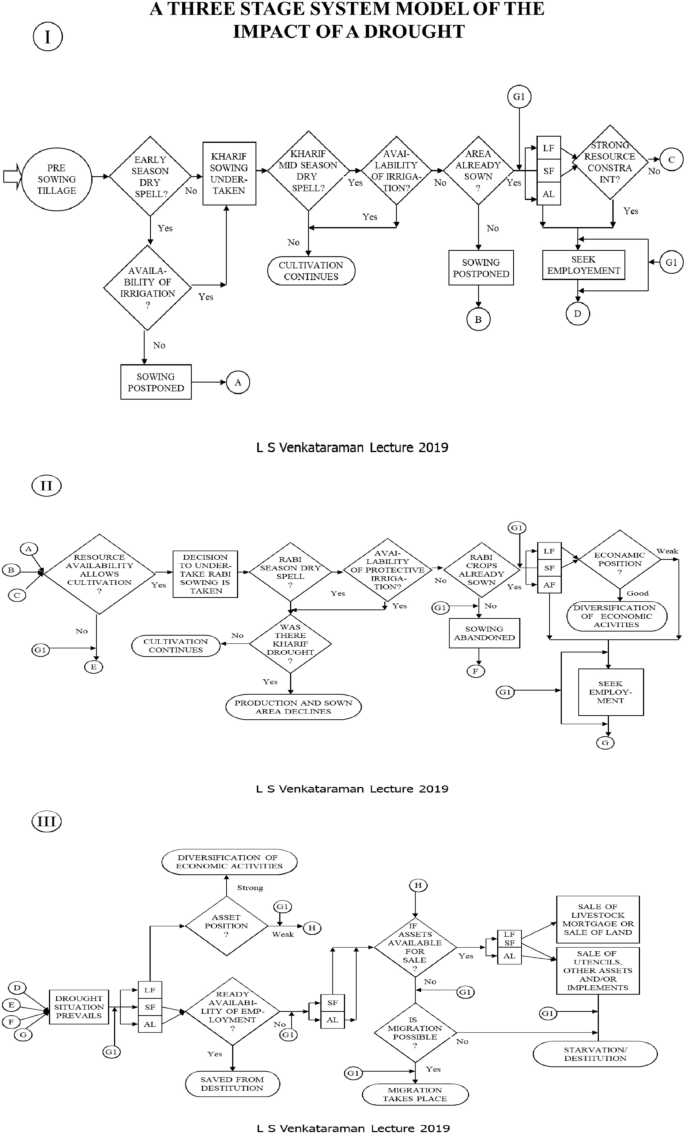

The crops start growing, and this is the initial stage of the crops when at least 2 to 3 showers are required for healthy crop growth as well as the application of fertilizers and manure. In this mid-season of crop growth, if there is a dry spell and if protective irrigation is available only, then the farming activities continue. In the absence of a dry spell also farming and activities continue. In case these two conditions are not satisfied and if the areas are already sown, the farmer suffers the loss of seeds, labour charges utilized for tillage, sowing and other activities. Initially, the farmer can postpone sowing and may get connected to either the place indicated as (A) or (B) to reach the second stage in the system diagram. The impact on the large farmers (LF), small farmers (SF) and agricultural labourers (AL) is different, and the availability of resources only dictates the further journey of the farmer. At this stage, the farming activities get connected to (C) (D) or (G1), as depicted in stage I.

The second stage in the system diagram picks up from (A), (B), (C) from stage 1 and the farming activities continue under the condition of availability of resources to continue on the second season cropping. It is necessary to bear in mind that the loss in the kharif season makes it difficult for the farmer to have working capital in hand and thus continue cultivation in the rabi season cropping. In such situations, many farmers tend to borrow from the moneylenders as already the crop loan is used out and the usual sources of credit are also exhausted in the first season. An early dry spell in the rising rabi season puts two conditions, namely: 1. Availability of irrigation and if there was no drought in the kharif that signifies that the economic condition of the farmer is better and therefore the cultivator continues with farming. 2. In case there was a kharif drought confronted earlier by the farmer, the economic condition of the household gets deteriorated. However, in case there is protective irrigation available the farmer continues with farming, but in case it is not available, and Rabi sowing has already taken place then the farmer suffers rabi season drought and loss of seeds fertilizers and other costs of cultivation. Again, survival to the third stage depends on the resource position of the farmers and those who cannot afford to sustain the usual lifestyle either migrate out of the village or seek employment in their own village or outside. At this stage, the farmer tends to diversify their activities. The third stage of the system diagram begins with connectors (D), (E), (F), (G) and (GI) from the earlier stages. If the drought prevails and if the said position is quite strong, then the farmer continues with normal economic activities or diversifies into other economic activities. In this position, the farmer’s availability for employment decides quite a bit about future sustenance. Otherwise, if there are household assets for the purpose of sale and at times even land, the cultivator resorts to the sale of livestock, household assets, jewellery, and even land. At this point of time the cultivator is absolutely helpless and the entire household economy is in a wreck. The economics of drought directly hinges on three important components. The first one is the timeliness of rainfall at the proper time and the availability of resources for continuing the cultivation. The second is the capability to diversify and enter into the labour market or other economic activities ensures survival of the household from a complete wreckage. Third, many times extreme steps are taken by the farmers by either committing suicide or migrating to far off places.

Drought can lead to economic wreckage only when the cultivator fails in his/her ingenuity to adjust to the situation of drought at the earliest and has non-diversified economic activities. The non-availability of water leads to the collapse of many economic activities and gives rise to epidemics like cholera, influenza and many such diseases due to the use of contaminated water. The other economic activities also get impacted and the prices of usual household goods as well as agricultural necessities increase substantially. That puts heavy pressure on the cultivator households. As seen above in the system diagram, the impact of drought varies according to its severity and the point of its incidence. However, a wide spread drought causes damage not only to the crop economy in terms of productivity, production and quality of crop output but other economic activities also. It also impacts the non-recoverable cost as there is a total loss of production, loss of animals and the usual professional activities besides non-availability of the basic requirements like drinking water, milk and of all work for the workers. The impact of drought is all pervasive as it has a spillover effect on related economic activities. The loss of crop activities exerts pressure on connected production and service sector activities thereby slowing down the process of increasing GDP. This is visualized in the form of troughs observed in GDP data during drought years. All these are shown in Table 12.

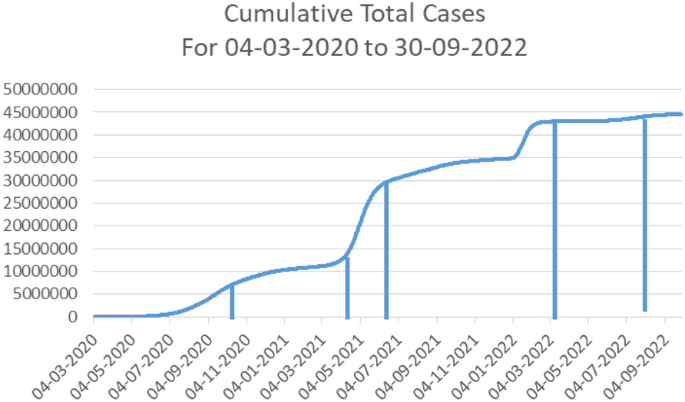

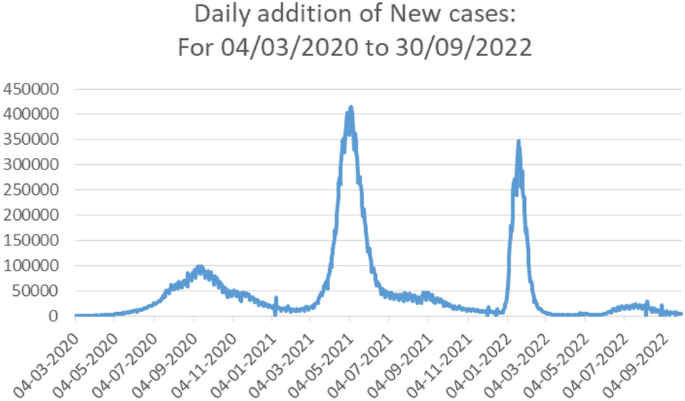

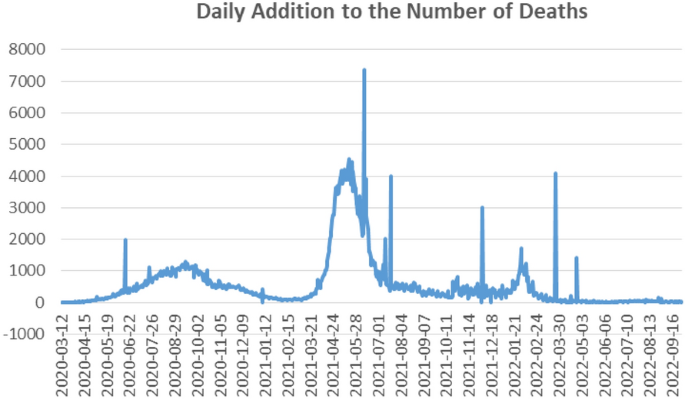

One can see there are more than three spurts in the number of cases, the first came in October 2020 and steadily kept increasing. The second spurt in the cases was experienced in April 2021 and immediately by the end of May 2021 the country experienced another spurt in cases. The real jump came as the third push in April 2021 followed in July 2021. The next spurt in the cases appeared in Jan 2022, and the cases got in control from February 2022. It will be erroneous to generalize (fed by the news papers) that the pandemic had struck in two waves, actually 15 September 2020 saw a peak of 97,894 cases soon to reach 103,558 on 3 April 2021. It was assumed to be the peak but was negated by a new number of 414,188 on the 5 of May 2021. It is clear from Fig. 5 that there were three strong spurts but more fluctuations. It is argued that the recovery period was from August 2021 to January 2022, during which Covid-19 cases began declining rapidly, and the economy started recovering from the shock. By April 2022, however, again a spurt was seen on 4 August 2022. As the severity of the waves of the pandemic began subsiding, many of the nationwide mobility restrictions were gradually relaxed from June 2021 and again reintroduced in January 2022. The daily increments in the cases are shown in Fig. 6 starting from 4 March 2020 to 30 September 2022 (Fig. 11).

The government initially responded with a partial lockdown and then clamped a full and strict lockdown. Almost all economic activities came to standstill. Economic activities in the informal sector and MSMEs (specifically dependent on casual workers) came to a complete cessation. The major dent was on the informal sector, out-sourced employees, the hospitality industry, travel, tourism, aviation, restaurants, entertainment, commercial real estate, small transport operators, etc. The workers dependent on these vocations suffered the real blow and unemployment shot up (CMIE 2020, 2021; Azim Premji University 2021). The economy underwent a severe contraction with severe suffering.

Indian economy had the first huge jolt from April to June 2020, with the country’s GDP declining by 24.4%. Followed by this in the second quarter of the 2020/21 (July to September 2020), the economy suffered another contraction of 7.4%. The mild reversal in the third and fourth quarters (October 2020 to March 2021) was not enough to cover the earlier loss. The contraction of GDP in India was (in real terms) 7.3% for the whole 2020/21 (RBI 2022a, b). The decline was the main reason for emboldening the picture of global inequality, which had been falling earlier but has started to widen again observed by some economists. While economies worldwide have been hit hard, India suffered one of the largest contractions. During the 2020/21 financial year, the rates of decline in GDP for the world were 3.3% and 2.2% for emerging markets and developing economies. Quarterly growth rates in Indian GDP in 2020–21 were − 24.4%, − 7.4%, 0.5% and 1.6%, respectively. The fact that India’s growth rate in 2019 was among the highest, caused the drop due to Covid-19 to be sharper and more noticeable. Unemployment has been one of the highly referred, important injuries inflicted by Covid-19. This was due to the lockdowns and the employers of the casual labourers did not care for them. Reverse migration was an inevitable outcome protected neither by their employer nor by the State Governments. Labour as a sector is under the concurrent list as given in the Constitution of India and, therefore, the State and Union Governments together carried the responsibility to ameliorate their livelihood shocks. India’s unemployment rate peaked at10.4% (CMIE, Jan 2020, p.5) indicating that the Govt of India could not manage this effectively compared to the reference group economies with similar per capita incomes. Possibly this was due to the composition of the Indian urban workforce where casualization of labour markets is pre-dominant. However, it should be noted that the data used for these rates were from CMIE and in the methodology of the survey, the CMIE report states “The sample size is 174,405 households (out of approx. 40 million households). Of this, 110,975 (out of approx. 11 million households) are urban households picked from 7920 CEBs of 322 towns, and, the remaining 63,430 (Approx. Out of 22 million households) rural households were picked from 3965 villages” (CMIE, Report, 2021, P. 193). This is certainly questionable, but probably at that time, there were no other sources available to get an idea of unemployment (Fig. 7).

The worst impact of the Covid-19 disaster was manifested in the number of deaths that occurred in this period. India lost 5, 28,655 persons up to 30 Sept 2022. This is from official records but many cases were not reported as death due to Covid. People carried a stigma attached to such declaring of death due to Covid and the neighbourhood stayed away from the entire family. Another severe agony was inflicted on the returning migrant labourers to their villages. There was a case reported from Kolhapur district that the migrants from the village were made to stay out of the village for a few days. During 1991 and 2011, there has been a significant increase in rural to urban migration from 21.2% in 1991–01 to 24.1% in 2001–11. This was due to the increase in economic activities at a very high speed in the urban locations. There were skyscrapers, new housing schemes, roads and other infrastructure, fly-over bridges, malls and many other casual employment opportunities that vindicated the Lewisian theory of rural–urban migration in search of higher wages. Unfortunately, this was without any preparations in urban areas to facilitate their stay in the urban cities.

The Government of India took quite a few steps to provide support to the affected population and these include some out of box measures such as direct spending and foregone/deferred revenue that included provision of in-kind (food; cooking gas) and in-cash transfers to lower income households; insurance coverage for workers in the healthcare sector; wage support and employment provision to low-wage workers, improving health infrastructure and increasing the number of hospital beds, ventilators, intensive care facilities and quarantine centres. In order to support businesses and shore up credit provision to several sectors of the economy and sections of the population, many of these measures are taken, but the implementation has many questions to answer.

Until August 2020, the Government of India had emphasized a supply-cantered strategy to boost GDP growth and the fall-out was squeezing the purchasing power needs. The employment losses due to the closure of the entire informal sector needed the generation of employment or providing some income support. In such a situation, it was certainly difficult to start any new employment programme and the MNREGS attendance also thinned down. As a result, the expenditure of the Union government on MNREGS declined between April and September 2020 as well as in April–September 2019. This was compensated by providing essential food articles to the poor and the reverse migrants. The government had little scope in expanding budgetary spending as the funds were directed towards the States as special grants.

Under the lockdown, complete disruption of all production activity was experienced with shrinking availability of capital, labour, and raw materials. All wholesale and retail markets as well as small shops were closed; even e-commerce was not operating. Under this pressure the MSMEs and all small businesses collapsed and these needed financing to restart, they downsized their businesses adding to unemployment. Along with this, the RBI announced a reduction in the policy rates and release of more liquidity and introduced a moratorium on term-loan repayments for six months. The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana (PM-KISAN) providing Rs 6000 per year began with a total allocation of Rs. 160 billion. A new scheme of Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) to old-age people, widows along with Ujjwala Yojana, and under Jan Dhan Yojana was speeded up amounting to Rs. 470 billion. On the employment front, MNREGA was extended to migrant workers and some workers in organized employment with an allocation of Rs. 922 billion. Besides, a special fund was created for construction workers of Rs. 310 billion. Direct food distribution through PDS was undertaken with an allocation of Rs. 35 billion. For the MSMEs, collateral-free bank loans of up to Rs. 3 trillion was announced. Along with this, aGovernment investment of Rs. 100 billion was initiated in funds that in turn will invest Rs. 500 billion in the equity capital of MSMEs. In addition to this and recognizing the stress on MSMEs a Rs. 200 billion subordinate debt was issued by banks and other financial institutions for strained MSMEs. Non-Banking Financial Companies were helped with Rs. 450 billion partial credit guarantee scheme, where the first 20% of the loss was guaranteed to be borne by the government. These were the new policy reforms including amendments to the Essential Commodities Act, liberalisation of investment norms for some sectors, etc.

Disasters strike with a very thin probability and these events could be placed at the tail end of the normal distribution. Therefore, predictability of any disaster is a difficult process and even with historical experience, we understand the region of incidence with a rough probability of likelihood in about a decade. Most of the major disasters in India are now about too much or too little water and the meteorological forecasts are available to the population only a few days ahead of the event. There are short and focus which are given a few hours before the event and then medium and extended forecasts on the time scale. However, we must confess that our understanding of hydro-metrological or geophysical phenomena is still far away from advanced predictability. Therefore, disasters like earthquakes, landslides, flash floods and cloud bursts happen when the population is totally unprepared resulting in huge human and animal casualties besides the devastation of property, crops and infrastructure. At least since a few decades, the regions classified as most disaster-prone have been identified and maps are prepared accordingly. Footnote 4 The Government of India has also opened offices of the National Disaster Management Authority along with the deployment of NDRF and SDRF in the regions. Even then, the administration fails to intake a rational decision while preparing for disaster management.

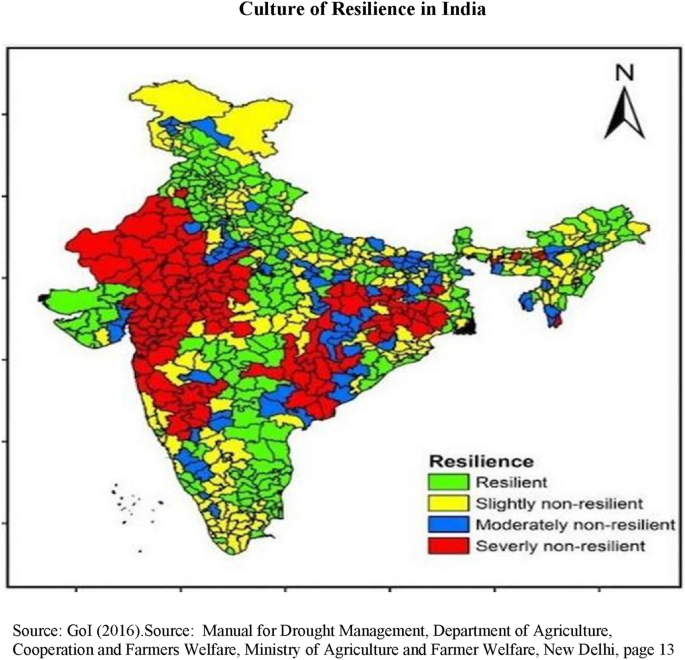

Certainly, disasters strike without sufficient warning and at times the events crawl into human life. Preparedness for the eventuality is one of the important steps before the disaster strikes. Even in Chanakya’s Arthshastra, it has been recorded that “There are eight kinds of providential visitations: These are fire, floods, pestilential diseases, earthquakes, famine, rats, tigers, serpents, and demons. From these shall the king protect his kingdom” (Shamasastry, p 294). Thus, the responsibility for ameliorating the conditions rests on the king or the government. It is necessary to note that the form of the government had changed from a kingdom to the Republic of India. It is not just a change of nomenclature, but such transformation enforces equal responsibility on the government and the people and that is most important to understand in today’s context. People’s participation in the preparedness as well as getting ideas from those who have been historically suffering disasters is essential. Our approach has always been top-down rather than learning from those who are at the bottom and suffer the most. This is expected in the republic of India (Map 6).

The map shows resilient, slightly non-resilient, moderately non-resilient and severely non-resilient districts in the country. This was prepared based on the perceptions of the disaster indicated by the population residing in the district. The level of resilience is largely decided by the probability of occurrence of extreme events and as some of the events occurred with very thin probability the perception of resilience differs significantly. Resilience is formed by three overlapping elements: (1) exposure (the shocks and stresses experienced by the system), (2) sensitivity (the response of the system), and (3) adaptive capacity (the capacity of the system with adaptive action) (Chakraborty and Joshi 2016). Like some of the coastal districts of Tamil Nadu and Odisha have a frequency of cyclones but their expectations are not formed based on the probability the population is not so much frightened of the event or rather thinks that precautionary steps can be taken at the time of the event itself. In the olden days, society was more cohesive and social interests preceded self-interests but during the commercialisation process when self-interest predominated, social insurance slowly vanished. Society as a whole is not taking collective decisions to protect from disasters. Panicky behaviour and herd mentality predominated in society and that increased the intensity of the damages. Information also plays a very important role in preparedness for such events. It will be essential to state here that every disaster causes huge devastation and loss of lives and livelihood. Many extreme disasters reset the development clock and every effort is forced to start right from the region. Infrastructure, houses, schools and roads and whatever comes in the way of the brute force of nature are destroyed and wrecked. It takes a long time to rebuild the physical assets but even longer to recoup the psychological impact on the population.

In the current situation, it should not be simply the responsibility of the government alone, but the entire rehabilitation and response work must be carried out by the people as well as the State. In India, we have accepted our Constitution and defined the nation as the Democratic Republic and therefore, the responsibility is equally on the people of the nation to meet the challenge thrown by the natural elements. Preparedness for the worst is the best kind of insurance besides the usual disaster insurance provided by financial intermediaries. The first step in such preparedness requires identifying the vulnerable regions at three levels, namely: (1) Seriously vulnerable, (2) Vulnerable and (3) Regions with low vulnerability. Similarly, in society also susceptibility differs according to the sensitivity of a social group and its social economic status. It is well known that disaster strikes fiercely at the most vulnerable. Therefore, poverty and destitution are quite common and located in these most vulnerable regions (Bhalla et al. 2022). The government has made significant efforts in putting several institutional frameworks to meet the disaster and ameliorate the after effects. Footnote 5 It is necessary that these institutions work with horizontal coordination enhancing efforts of each other. Therefore, a coordination Body like NDC involving State Home Ministers with Non-Government Expert Participation is necessary to take a periodic overview. The coordination or joint meetings of NEC and NCMC are also necessary to discuss resilience. Actually, equal responsibility and liability also lie with the private sector operating in the region. Community participation; cooperation of local administration with NDRF and Permanent Disaster Management Funds and regular contributions from the States and Central Budget are essential components.

A final plan to meet the requirements of managing every type of disaster in India requires integration of disaster mitigation and preparedness in development programmes with multi-sectoral/inter-departmental coordination and multi-hazard approach in disaster management planning. An important component is the preparedness of society through public awareness and community capacity, to cope with the hazards, reduce dependence on the government and build a culture of self-help. It needs to be seen if the Task Force for Review of DMA Recommendations-2013 as well as the NDMA Plan of 2016 is implemented, and that step can go a long way if executed scrupulously. In all, full transparency of plans and actions needs to be maintained with clear documentation. Integration of State and National DM Plans for ensuring food security and establishing quick shelter facilities is a vital component. In any disaster, transportation gets impacted; therefore, establishing proper transport networks is crucial. Preparedness at the household level also needs to be looked into in the capacity building programmes. Finally, it is a battle of wits between human intelligence and Pancha Mahabhutas; therefore, disaster strikes without much warning throwing a challenge of ingenuity for defence with all the preparations to the human race.

Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

Soil piping is a naturally occurring hydraulic process that leads to the development of macrospores (large air filled voids) in the sub-surface.

This section draws from my earlier work (Deshpande 2022).Maps are the best tools which incorporate many dimensions of any concept in a simple two-dimensioned diagram.

National Safety Council of India-04–03-1966; National Centre for Disaster Management-1995; India Disaster Resource Network-2004; National Institute for Disaster Management-2004; National Disaster Management Act-2005; State Disaster Management Authorities-2005; National Disaster Response Force-2006; National Policy on Disaster Management 2009; National Disaster Management Plan-2016,18,19; National Emergency Operation Centre-2020.

I thank my guru Prof M V Nadkarni, Hon Professor, ISEC, Dr V S Prakash, former Director KSNDMC, and Dr Khalil Shaha for help as well as many inputs.